China’s ‘Artificial Sun’ Breaks Nuclear Fusion Record with 1,000-Second Plasma Loop

China’s nuclear fusion reactor, known as the “artificial sun,” has achieved a significant milestone by breaking its own record and advancing humanity closer to nearly limitless clean energy.

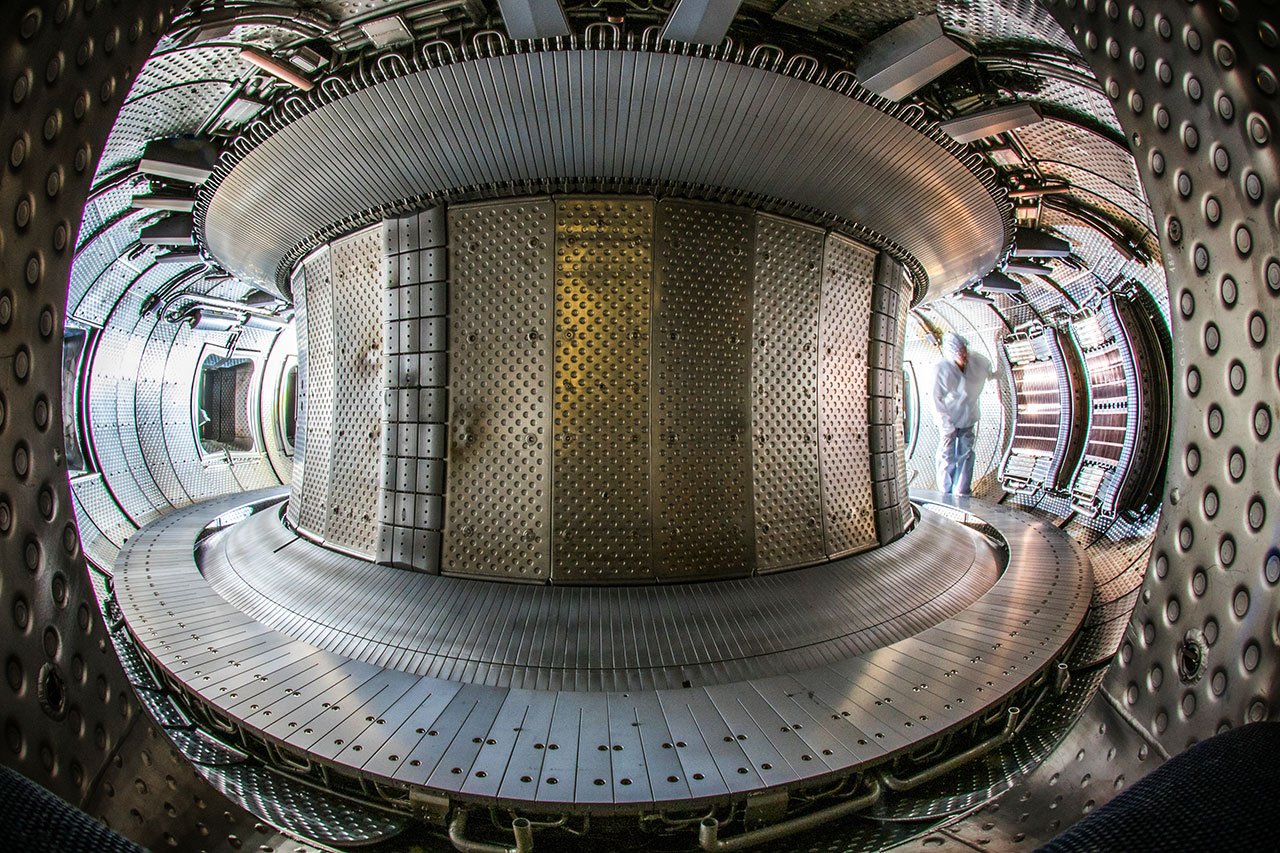

The Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (EAST) reactor maintained a stable and highly confined loop of plasma — the high-energy fourth state of matter — for an impressive 1,066 seconds on Monday (Jan. 20), more than doubling its previous record of 403 seconds, according to Chinese state media reports.

How Nuclear Fusion Works

Nuclear fusion reactors are called “artificial suns” because they generate energy in a way similar to the Sun — by fusing two light atoms into a single heavy atom through intense heat and pressure. Since Earth’s reactors lack the immense pressure found in the Sun, scientists compensate by using temperatures that exceed those of the Sun.

Nuclear fusion offers the potential of an almost limitless energy supply without greenhouse gas emissions or significant nuclear waste. However, researchers have been working on this technology for over 70 years, and it is progressing slower than needed to address the climate crisis. While experts predict fusion energy could become viable within decades, it may still take much longer.

A Step Toward Sustainable Energy

Although EAST’s new record does not immediately pave the way for what is often called the “Holy Grail” of clean energy, it represents a crucial step toward a future where fusion power plants can generate electricity efficiently and sustainably.

EAST is a magnetic confinement reactor, or tokamak, designed to sustain plasma continuously for extended periods. While reactors like this have yet to achieve ignition — the point at which nuclear fusion generates enough energy to sustain its own reaction — the recent achievement brings scientists closer to maintaining long-lasting, confined plasma loops essential for future power generation.

“A fusion device must achieve stable operation at high efficiency for thousands of seconds to enable the self-sustaining flow of plasma, which is essential for the continuous power generation of future fusion plants,” said Song Yuntao, director of the Institute of Plasma Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in a statement to Chinese state media.

Challenges and Future Prospects of Nuclear Fusion

Nuclear fusion has long been considered the clean energy of the future, but several challenges still stand in the way of its practical implementation.

EAST and Global Fusion Efforts

EAST is one of several nuclear fusion reactors worldwide, but currently, all such reactors consume more energy than they generate. In 2022, the U.S. National Ignition Facility’s fusion reactor achieved ignition in its core using a different experimental approach compared to EAST, relying on rapid bursts of energy. However, the reactor as a whole still required more energy than it produced.

Tokamaks like EAST are the most widely used type of nuclear fusion reactors. These reactors heat plasma and confine it within a donut-shaped chamber, known as the tokamak, using powerful magnetic fields. To achieve its latest record, EAST underwent several upgrades, including doubling the power of its heating system, according to Chinese state media.

Related Developments in Nuclear Fusion

- UK Nuclear Fusion Reactor Sets New Energy Output Record

- Physicists Solve Nuclear Fusion Mystery with Mayonnaise

- Fusion Reactor ‘Breakthrough’ is Significant but Far from Practical Use

Collaborative Global Efforts

The data gathered from EAST will contribute to the development of other reactors in China and around the world. China is an active participant in the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) program, which includes dozens of countries such as the U.S., U.K., Japan, South Korea, and Russia.

Currently under construction in southern France, the ITER reactor will house the world’s most powerful magnet and is expected to commence operations by 2039 at the earliest. ITER will serve as an experimental platform to achieve sustained fusion for research purposes, potentially paving the way for future fusion power plants.

“We hope to expand international collaboration via EAST and bring fusion energy into practical use for humanity,” said Song Yuntao, director of the Institute of Plasma Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Post Comment